What is Google Analytics 4? GA4 vs. Universal Analytics: A side-by-side comparison and how does it differ from Universal Analytics? 1.part

Universal Analytics has already seen its sunset in July 2023, paving the way for its successor, Google Analytics 4 (GA4). Since becoming the standard for new properties on Google Analytics as of October 14, 2020, there hasn’t been a widespread eagerness among marketers and web developers to transition from UA to GA4.

GA4 introduces a significantly different operational framework compared to UA, bringing along new and improved features but also facing criticism for certain bugs and the absence of some popular UA features. This article will explore all major distinctions between these two platforms (Universal Analytics and Google Analytics 4) and we will get also into more detail to show you what new opportunities GA4 offers.

But first, we will get a little bit of the history of this amazing web tracking tool.

Brief history of Urchin/Google Analytics

Our story begins in the late 1990s, a time when the internet was rapidly expanding and businesses were just beginning to realize the potential of an online presence.

Urchin Analytics began its journey in the realm of web analytics as a product of Urchin Software Corporation, founded in 1995. The company, focusing on the web statistics and web analytics field, developed Urchin as a software solution to help businesses understand and interpret web traffic data. In 1998, Urchin Software Corporation emerged, as a pioneer in the field of web analytics. Their product, Urchin, was groundbreaking, offering website owners invaluable insights into visitor behavior.

As the internet evolved in the early 2000s, Urchin Software Corporation adapted by introducing a new product – Urchin On Demand. This service marked a significant shift from traditional, software-based analytics to a more accessible, service-based model. Urchin On Demand allowed users to monitor and analyze their web traffic through a hosted solution, eliminating the need for installing complex software on their own servers. This move was pivotal in making web analytics more user-friendly and widely accessible. Urchin on Demand, was one of the early tools available for website traffic analysis.

The potential of Urchin Analytics did not go unnoticed by the tech giant Google. In April 2005, in a move that would significantly shape the future of web analytics, Google acquired Urchin Software Corporation. This acquisition was a strategic step for Google, as it sought to expand its footprint in the world of online analytics and advertising.

The legacy of Urchin Analytics is thus deeply intertwined with the evolution of web analytics as a whole, marking a significant chapter in the history of how businesses understand and interact with their digital audiences.

First (former Urchin) team day at Google, April 21, 2005 after acquisition.

First website tracking software Urchin and its evolution and Urchin Software Corporation story

TL; DR: Urchin Software Corporation, originating in San Diego, CA, was co-founded by Paul Muret, Jack Ancone, Brett Crosby, and Scott Crosby. In April 2005, Google acquired the company, transforming Urchin into “Urchin from Google,” and eventually evolving it into Google Analytics. With the many anniversaries of this acquisition having recently passed, it seemed an opportune moment to document the company’s history for future reference. This account may not captivate those unconnected to its journey; it’s more a personal closure of that chapter.

Perhaps, this story also subtly indicates that success doesn’t always require massive initial funding or rapid growth. Sometimes, a more modest approach with gradual progress can lead to significant achievements.

Founding of Urchin Software Corporation

In the late months of 1995, the seeds of what would become Urchin Software Corp. were sown by two post-college roommates, Paul Muret and Scott Crosby, in the Bay Park neighborhood of San Diego. Paul, who had been working in the Space Physics department at UCSD, stumbled upon the world of HTML 1.0 while uploading the department’s syllabus online. This exposure sparked an idea in him, a vision of a business opportunity to create websites for other businesses.

One evening, Paul returned home, brimming with excitement about this newfound opportunity. To illustrate his point, he showed Scott a simple website he had created for UCSD, featuring bright blue text on a grey background, with some of the text possibly even blinking in an early web aesthetic. Convinced by Paul’s enthusiasm and the potential in this nascent internet era, the two embarked on drafting a business plan.

Their plan, a blueprint for a venture into the digital frontier, was presented to Scott’s uncle, Chuck Scott. Chuck, a figure of financial means, saw promise in the young entrepreneurs’ vision. He agreed to invest $10,000 in their new company and even provided them with a small desk space in a corner of his office at C.B.S. Scientific. Little did he know, it would be a considerable time before this investment brought its fruit, marking the humble beginnings of a journey that would significantly impact the digital analytics world.

In the wake of receiving financial backing from Chuck Scott, the fledgling company embarked on its journey by purchasing a Sun SPARC 20 for server duties and securing an ISDN line, a significant expense at the time. The office computers were interconnected using 10base2 networking, a system that relied on coaxial cables with twist-lock fittings, reminiscent of TV cables but now seen as antiquated.

The first Urchin webserver, running at 50 MHz, was ~$3200 in 1995 money. That was about 1/3 of the total raised capital in that time for Urchin Software Company.

Paul and Scott, the duo behind this venture, began the arduous task of customer acquisition. Their clientele grew gradually, mostly comprising small businesses that paid a modest monthly fee. Among their early clients were Cinemagic, a vintage movie poster company run by Herb and Roberta, and ReVest, a financial startup. The owner of ReVest was notably averse to using email, leading to website edits being communicated through lengthy thermal-transfer faxes that unspooled across the office floor each morning. Another notable client was a lesser-known division of Pioneer Electronics, specializing in the production of LaserDiscs, a format already considered archaic at the time.

Buoyed by these early successes, the company leased office space in a modest brownish-green building located in the faux-historic, theme park-like area of Old Town, San Diego, not far from Rockin’ Baja Lobster. The office could accommodate up to four desks, five if the vestibule was counted, possibly intended for a secretary. In 1997, the company welcomed a new member, Brett Crosby, Scott’s younger brother, marking a turning point as the business began to gain momentum. They managed to secure contracts with two of the larger local employers: Sharp Healthcare, a hospital system, and Solar Turbines, a power generation subsidiary of Caterpillar.

Despite these significant contracts, the company still catered to numerous small clients, hosting their websites on a single web server and charging a recurring fee. To accurately bill for bandwidth usage—a costly resource at the time—Paul developed a simple log analyzer. This tool not only tallied bytes transferred but also provided a user-friendly web interface, tracking referrers, “hits”, and pageviews. This innovation laid the groundwork for the first version of Urchin. After further enhancements, including date-range features and user authentication, Urchin was showcased to customers, receiving generally favorable feedback.

This period was a critical one for the company, with the deal from Solar Turbines alone, bringing in $10,000 per month, playing a vital role in keeping the business afloat for over a year. This early phase of struggle and gradual success was the foundation upon which the future of web analytics was built.

In 1997, the team behind what would become Urchin Software Corp embarked on their first-ever trade show adventure. In a creative twist, they borrowed giant blue light boxes from an underwear startup. These boxes, made of 1-inch thick particle board, were notably heavy and cumbersome, adding a unique challenge to their trade show debut.

To add a bit of flair to their booth, they enlisted the help of friends who, intrigued by the novelty of an internet trade show, volunteered to assist for the day. These friends, playfully referred to as “booth babes,” brought lively energy to the booth. However, the long hours and bustling environment of the trade show proved to be more demanding than anticipated. As a result, their initial enthusiasm vanished (probably), and they decided not to volunteer for such events again :-). This first trade show experience was a mix of improvisation, camaraderie, and learning, marking a memorable step in the company’s early journey.

In the late 1990s, a pivotal moment arose for the company that would later become Urchin Software Corp, thanks to a connection through Brett Crosby’s girlfriend, Julie, who worked in the advertising and web development industry. Julie was employed by Rubin Postaer Interactive (RPI), a company that still exists today, a subsidiary of the prominent Los Angeles-based RPA (Rubin Postaer and Associates), which managed the Honda.com account. It was discovered that Honda.com, then using WebTrends for web analytics, struggled with processing their daily Apache access logs within a single day, leading to a backlog.

Seizing this opportunity, the team managed to acquire a few days’ worth of server logs from Honda.com to process as a demonstration. Impressively, they completed the task in approximately 30 minutes, a feat that led to them becoming the web analytics solution for American Honda. This success marked a turning point, indicating the potential to build a business around Urchin’s log processing technology.

Around the same time, Jack Ancone joined the team as the CFO and relocated to San Diego. The company then moved into an office at 2165 India St.

The Urchin Software Company moved into an office at 2165 India St. This is how it looked like.

In the early days of 1998, a significant milestone was reached for the team behind Urchin Software Corp. They celebrated their first sale of the “Pro” version of Urchin, priced at $199. This moment marked a turning point, prompting a strategic shift in their business model. They decided to focus solely on software, divesting themselves of their hosting and web development services. These segments were handed over, without any financial gain, to a local web development shop. This bold move transformed Urchin company into a pure software company, a transition met with enthusiastic high-fives all around.

To support this new direction, the Urchin Software Company needed additional funding. They tapped into their family networks and collaborated with a boutique venture capital firm, Green Thumb Capital from New York City, brought in by Jack. This effort successfully raised $1 million, increasing their total external capital to approximately $1.25 million. Despite future attempts, this would be the last of their fundraising, except for a manageable debt of around $400,000, which was later repaid with interest and warrants. Green Thumb Capital, to their credit, never pressured them for returns, likely as surprised as anyone when Google later acquired Urchin.

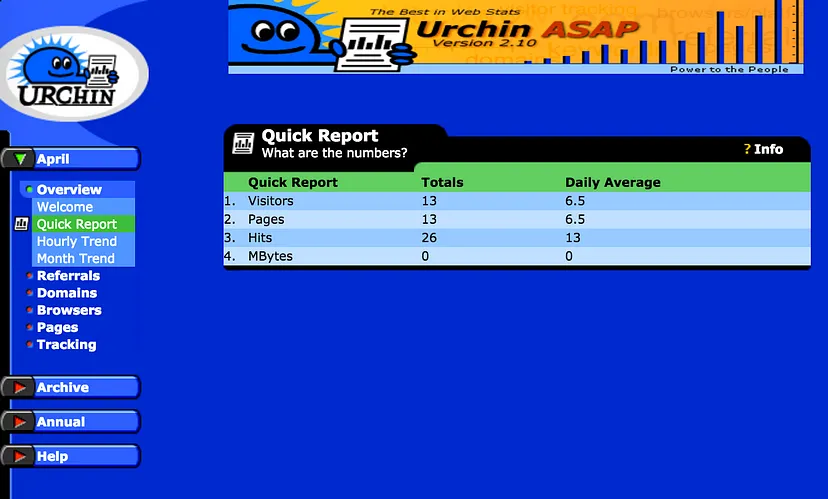

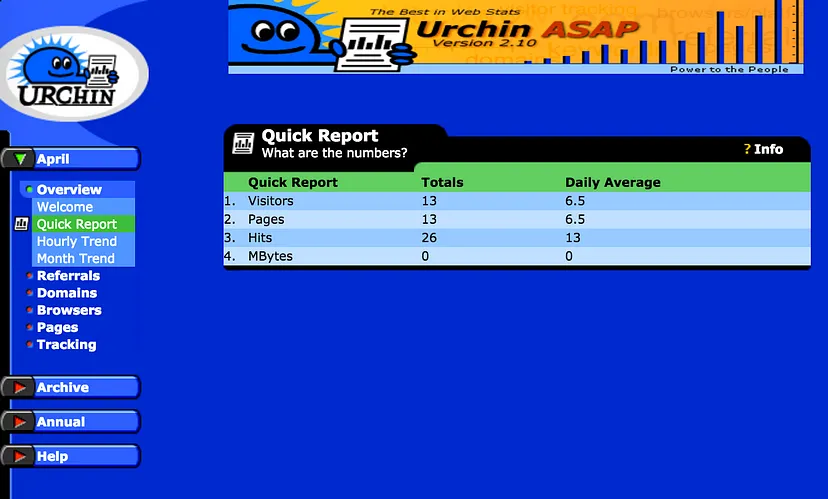

During the late 1990s, as they navigated the challenges of selling enterprise software, the team opted for an unconventional, advertising-based strategy to capture market share. In an era where internet companies were often valued by the number of “eyeballs” they attracted, they released Urchin ASAP, a free version of their software supported by banner ads, alongside Urchin ISP. Both versions were tailored for hosting operations. The Urchin Software Company team thought they could make a significant fraction of a cent per click on these ads, on top of some infinitesimal CPM. Although the banner ads didn’t generate significant revenue, they did succeed in gaining valuable exposure.

One of the Urchin ASAP banner ads, which advertised itself when no one else wanted the space

This approach, combined with the quality of their software, set the stage for their first major breakthrough in the industry.

In the old days of the internet, a time when Tumblr and Blogger were still on the horizon and Geocities was a household name, there existed a platform known as Nettaxi. This relatively obscure service claimed to host a staggering 100,000 “sites,” a figure that intrigued the creators of Urchin. Seeing Nettaxi as a potential goldmine for user engagement, they struck a unique deal: Urchin’s sophisticated web analytics tools would be offered to Nettaxi completely free of charge, in exchange for the ad revenue generated from the traffic of all these sites. The financial outcome of this arrangement? A few cents, if there were any, but the real value, however, was in the claim that Urchin company now could say – they were servicing 100,000 sites. This statistic significantly boosted their market presence.

In a move reminiscent of Google’s playful logo variations, the Urchin team introduced their own creative twist: the “Urchin of the Day.” This quirky feature, which involved changing the Urchin logo in the interface’s upper-left corner, was more than just a fun gimmick. It was an attempt to forge a closer bond with their user base. Whether it achieved this goal is debatable, but it certainly kept its designer, Jason Collins, busy and entertained for a considerable period. His creations, ranging from whimsical to downright hilarious, are still remembered fondly. Among these was a special design by Shepard Fairey, later famous for his iconic “Obama Hope” poster, who contributed a “Power to the People” version of the Urchin logo.

Urchin of the Day – created by Jason Collins (designer/graphic) – his creations weren’t just static images; they were dynamic, animated GIFs that brought a sense of life and movement to the company’s interface. With each new design, Jason’s talent shone, blending his love for cars with his flair for digital artistry, making the “Urchin of the Day” a much-anticipated reveal among the team and clients alike.

In the late 1990s, a small, ambitious team led by Brett Crosby, the VP of Sales and Marketing at Urchin Software Corp., was on a mission to elevate their latest creation, Urchin 2.0, into the spotlight. Their target? Earthlink – a giant in the internet service provider industry, nearly rivaling AOL in size and influence. The challenge, however, was making contact with someone influential within such a colossal organization. Undeterred, Brett resorted to the simplest yet most persistent method: repeatedly submitting inquiries through Earthlink’s web form, a testament to determination over sophistication.

“We had no idea how to reach anyone important at a place like that, so Brett did the natural thing and filled out a web form. Again, and again, and again. He must have submitted that thing 20 or 30 times. Finally, he got a response. Rob Maupin, VP of hosting (or something similar) agreed to a meeting. We were stunned.”

After what seemed like an endless stream of attempts, their persistence paid off. Rob Maupin, a high-ranking executive at Earthlink, responded, agreeing to a meeting.

So they were about to pitch to one of the internet’s behemoths. In their best vehicle, Brett’s old but reliable Mercedes bought for that purpose for 4,000 USD, they went to Pasadena, while Scott Crosby, another key figure in the company, stayed at the office, partly out of managerial duty, partly out of sheer intimidation.

The meeting with Rob Maupin was a reality check. He bluntly criticized the Urchin 2.0 interface for its overwhelming use of blue, a fair point that the team had to concede.

Too blue blue blue blue blue Urchin 2 – version, which was used in presentation for Earthlink

Despite this, Maupin saw potential in Urchin’s speed and efficiency, crucial factors for web hosting services these days (and nowadays also). After accommodating Earthlink’s requests for modifications, Urchin struck a deal that would become a cornerstone of their success: $4,000 per month for unlimited use of Urchin software across all Earthlink-hosted websites.

By 2001, the company had evolved into Urchin Software Corporation, and it was time to seek additional funding. The process of pitching to venture capitalists was grueling and distracting, but eventually, they managed to secure commitments from two reputable firms. The funding, however, was scheduled to be finalized on September 12th, 2001 – a day after the world-changing events of 9/11. The aftermath of the tragedy put the investment on hold indefinitely.

Having already expanded in anticipation of the $7 million investment, Urchin found itself in a precarious financial position. They had to make drastic cuts, including laying off 12 employees and giving up office space, a day they somberly referred to as Black Friday. Facing a dire cash flow crisis, they had no choice but to seek loans from benefactors Chuck Scott and Jerry Navarra, who provided the much-needed funds in exchange for interest and warrants. This period marked a challenging phase for Urchin, with drastic cost reductions and employees voluntarily taking significant pay cuts to keep the company afloat. Despite the hardships, the team’s resilience and dedication kept Urchin alive, even when hope seemed fleeting.

The business was divided into three main areas: web development, hosting, and software development, following a strategy of diversification.

In January 1998, the company celebrated its first sale of the “Pro” version of Urchin for $199. This milestone was followed by a strategic shift to focus solely on software development, leading to the abrupt discontinuation of hosting and web development services. The company transitioned into a pure software company, a decision marked by a symbolic high-five.

To support this new direction, the team raised $1 million through family connections and a boutique venture capital firm, Green Thumb Capital of NYC, bringing their total outside capital to approximately $1.25 million. Despite later attempts, this would be the last of their fundraising, except for a small amount of debt financing.

In an effort to capture market share in the late 1990s, the company adopted an advertising-based approach, releasing Urchin ASAP, a free counterpart to Urchin ISP, both aimed at hosting operations. The plan was to generate revenue through banner ads displayed at the top of each page, capitalizing on the era’s emphasis on “eyeballs” over profitability. However, this strategy did not yield significant financial returns, but it did provide valuable exposure and helped establish the software’s reputation in the market. This approach laid the groundwork for the company’s first major breakthrough in the world of web analytics.

In the early 2000s, the tech industry was still reeling from the aftermath of the dot-com bubble burst. Revenue streams were inconsistent, and growth was slower than anticipated.

The company’s primary revenue source had been substantial annual licensing deals, often involving lengthy and complex negotiations. One of their most significant contracts, exceeding $1 million, was secured by Jack Ancone with Cable & Wireless, a major player in the global telecommunications and hosting industry. However, despite these promising deals with companies like Winstar, KeyBridge, and Worldport, payments often fell through as these seemingly resource-rich companies faced their own financial limitations.

To invigorate sales and streamline processes, Urchin made a strategic decision to simplify their enterprise deals with hosting companies. This new approach, although less lucrative in the short term, was based on the modest deal they had previously struck with Earthlink. The new Site License Model (SLM) was straightforward: hosting companies would pay $5,000 per month for each physical data center, receiving unlimited access to Urchin software under a simple, one-page contract, no legalese, and nothing really to negotiate.. This model quickly gained popularity, attracting major hosting companies in the US and Europe, including Rackspace (now part of IBM), Everyone’s Internet (aka EV1 Servers), The Planet, and Mediatemple and many others.

By the fall of 2003, these deals had propelled Urchin into a cashflow-positive position. They were also successfully selling individual licenses to self-hosted organizations, including Fortune 500 companies and numerous university systems.

The sales team, having been significantly reduced during the company’s financial struggles in 2001, was small but mighty. Paul Botto, Nikki Morrissey, and Megan Cash, who had worked without pay during the toughest times, played a crucial role in Urchin’s recovery. Their efforts, combined with a new commission model that offered low base pay but high commission rates, led to a significant boost in sales.

Paul and Megan eventually joined Google, while Nikki chose a different path.

Urchin 4 had an easter egg that no one ever found. If you clicked a random “rivet” in the sexy brushed aluminum interface, you’d be treated to a photo of the illustrious Urchin dev team: Doug Silver, Nathan Moon, Paul, Jonathon Vance, Rolf Schreiber, and Jim Napier. Most of these guys are still at Google (date to Aug. 2016).

Urchin’s international expansion had its ups and downs, including a failed attempt to establish an office in Tokyo. However, the launch of a channel program, particularly in markets where English wasn’t the primary language, proved to be a wise move. Japan, for instance, became a strong market for Urchin, thanks to the efforts of Jason Senn, who managed the channel program and also took on the role of chief office builder.

Product-wise, Urchin was evolving. If Urchin 2 opened doors and Urchin 3 maintained standards, Urchin 4 was a game changer. It featured a modern, Apple-esque design and introduced the Urchin Traffic Monitor (UTM). The UTM was a pioneering method that combined Apache or IIS log files with cookies, enabling the identification of unique visitors. This hybrid approach of using both log files and cookies set Urchin apart from competitors who relied solely on one method or the other. Urchin’s innovative approach laid the groundwork for more advanced web analytics practices, foreshadowing the capabilities of future tools like Google Analytics.

Once upon a time in the tech world, Urchin Software Corporation released Urchin 4, a product that continued the company’s quirky tradition of supporting an incredibly diverse array of platforms. If you ever stumble upon Google’s Urchin 4 help page, you’ll be amused to see the list of supported operating systems, including the obscure Yellow Dog Linux. The team at Urchin had a vision: they believed that by supporting a wide range of platforms, they might break into major corporations or universities that used less common systems like AIX or HP-UX. However, reality proved different, with most customers opting for the Linux or Windows IIS versions.

The team’s enthusiasm for diverse platforms led them to acquire various servers from eBay, enjoying the challenge of getting Apache and a compiler running on each unique system. They even dabbled with a NeXT version, though they steered clear of DEC after struggling to boot up the machine.

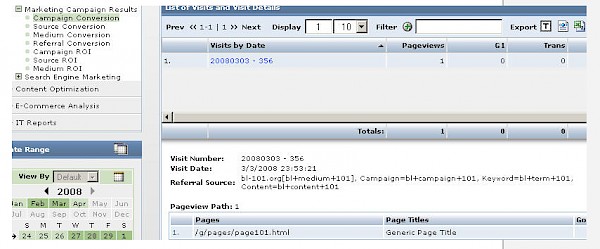

Urchin 4 marked a turning point for the company. It was the first version that they felt could truly compete with any other product in the market, not just in back-end performance. But it was Urchin 5 that took things to a whole new level. It was a powerhouse of a product, albeit a bit overwhelming with its layers of menus and submenus. It was a dream for analytics enthusiasts, packed with features like e-commerce tracking, the Campaign Tracking Module, and multiserver versions. Urchin 6 introduced a groundbreaking feature: individual visitor history drill-down, a capability so sensitive that Google later decided to remove it entirely.

Until Urchin 5, the company had operated on a traditional software licensing model. But by 2004, it was clear that a hosted version was necessary. So, they invested in servers, upgraded their T1 line, and launched Urchin 6, available both on-premises and as a hosted service. This new business model was an instant success, with companies willing to pay for the convenience of not having to manage the software themselves.

By the summer of 2004, Urchin boasted the largest installed base among web analytics vendors, measured by the number of websites using their product. Tradeshows, once a daunting task, became enjoyable events for the team. It was at the Search Engine Strategies 2004 in San Jose that Urchin caught the eye of Google. Wesley Chan, a Product Manager, and David Friedberg from Corporate Development, were on the lookout for a web analytics company. Despite the unconventional approach of Urchin, they saw potential in what they found.

Paul Botto, Scott Crosby, and Brett Crosby, at Search Engine Strategies 2004, San Jose, where they first met with the Google people.

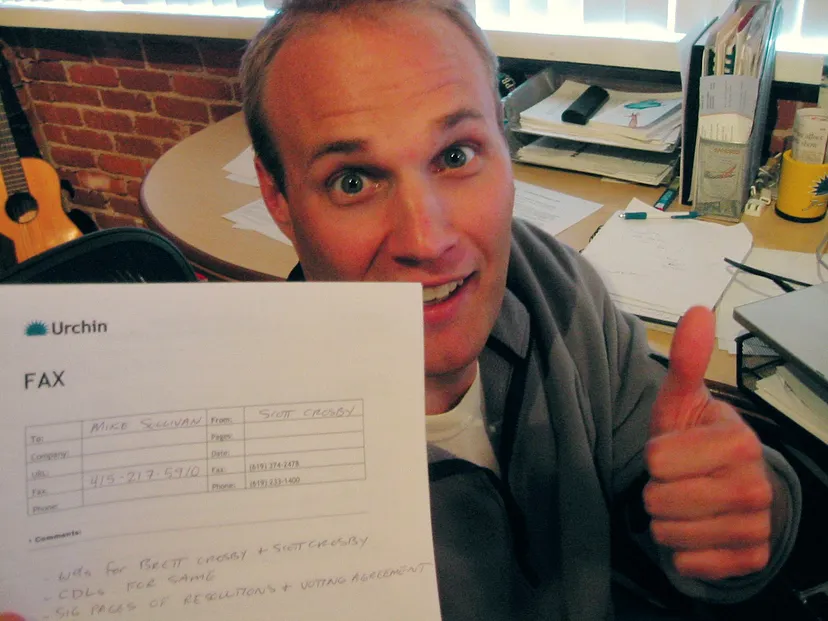

Brett Scott prepares to “fax” the signed acquisition agreement back to Google. By this time Urchin Software Companywere sufficiently profitable that it was a tough decision to sell. Brett Scott signed the actual, final paperwork in a tuxedo about 30 seconds before walking down the aisle at his wedding.

In a tale of ambition and success, a small but innovative company named Urchin Software Corporation found itself at a pivotal moment. Just a few weeks after catching the attention of tech giant Google at a tradeshow, an offer was made to acquire Urchin. This period was marked by interest from various players in the tech world, including WebSideStory, a public company at the time, which even offered a higher bid. However, the Urchin team believed Google was the right choice (and time showed that it was the right decision).

The process of selling Urchin to Google, however, was far from smooth. It was expected to conclude shortly after Google’s IPO in late 2004, but the legal intricacies, particularly around intellectual property and patent risks, made it a nerve-wracking experience. The founders were personally liable for any potential patent infringements, a daunting prospect given their new association with a major player like Google. The deal was finally sealed in April 2005, by which time Google’s stock had doubled, impacting the financials of the deal.

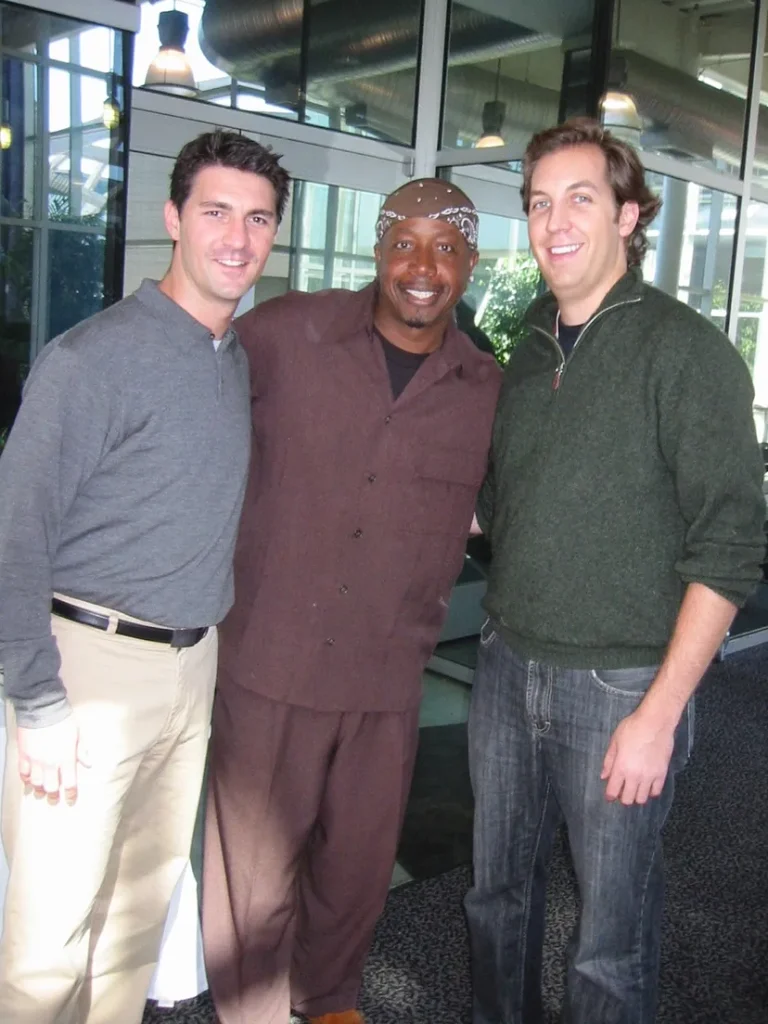

Joining Google for Urchin team in 2005 was a unique experience. The company, still in its relative youth with around 3,000 employees, had a vibrant culture. Everyone could gather for a single, grand holiday party, and celebrities like MC Hammer were a common sight.

Jack, MC Hammer, and Chris Sacca (2005).

On their first day, the Urchin team met with Eric Schmidt, Google’s CEO at the time. Schmidt immediately recognized the potential of Urchin’s web analytics in relation to Google’s Adwords. He remained a supportive and accessible figure throughout their integration into Google. Brett Crosby, who later became Senior Director of Marketing at Google, even had an office next to Schmidt.

The Urchin team was initially placed in the “fishbowl” of Building 42 at Google’s Mountain View campus, in close proximity to Google’s founders, Larry Page and Sergey Brin. Sergey, known for his eccentricities, had a laser engraver in his office, complete with an air duct for venting gases. They also shared the space with Mike Stoppelman, a new Google engineer whose brother would soon found Yelp.

As Google prepared to launch Google Analytics, the rebranded Urchin product, in 2005, there was apprehension about its reception. Wesley Chan, the Google Product Manager leading the integration, initiated a daily “war room” to ensure the product’s success. The team was given specific objectives and tight timelines to meet. The effort involved educating the rest of Google about the product, with team members touring Google offices nationwide.

When “Urchin from Google” was announced as a free service for any website in the world, the response was overwhelming. The demand was so high that it strained Google’s infrastructure, leading to a temporary shutdown of new signups. This was a problem of success, but it frustrated many. Eventually, signups were reopened using an invitation model, and Google Analytics began its journey to becoming the ubiquitous tool it is known today.

In the grand narrative of tech acquisitions, Google’s purchase of various companies stands out. Among these acquisitions, some, like YouTube and Keyhole (which became Google Earth), soared to great heights. Others, however, like Dodgeball, faded into obscurity, victims of the complex dynamics within a large corporation. This phenomenon, partly due to Google’s acquisition strategy and partly due to the inertia and fog that often accompany big companies, led to many promising ventures dissolving into the corporate ether.

For acquisitions under a certain threshold, rumored to be around $50 million, the decision-making process was startlingly straightforward: a single VP’s approval could seal the deal. However, once these companies were integrated, they often found themselves adrift in the vast sea of Google’s operations. Without a high-level champion or a clear path to significant revenue generation – often benchmarked at around $100 million annually – these acquisitions struggled to maintain their identity and purpose.

Urchin, the company behind what would become Google Analytics, was one of the fortunate few. It found powerful allies in Wesley Chan, a product manager who recognized the need for robust analytics to bolster Adwords, and Eric Schmidt, then CEO of Google. Schmidt quickly grasped how web traffic analysis could enhance Adwords’ effectiveness. A few years later, an internal study at Google, conducted by a team of quantitative analysts, demonstrated a substantial increase in ad spending across a wide range of customers, validating the strategic importance of the acquisition.

As time passed, the original team from Urchin began to disperse within Google. Some left the company, but a significant number remained, continuing to contribute to Google Analytics. Notably, Paul, a key member of the Urchin team, rose to become a senior VP of engineering, overseeing not just Google Analytics but also the display ads segment.

You can read the whole Urchin Software Company story directly from the co-founder of Urchin (brother of the next founder Brett Scott): https://urchin.biz/urchin-software-corp-89a1f5292999

Seven Urchin versions

There were 7 different product versions of Urchin (the predecessor of the later well-known Google Analytics/Universal Analytics).

Urchin 1: The early days of a web analytics pioneer

In the mid-1990s, the digital landscape was burgeoning, and amidst this backdrop, Paul Muret and Scott Crosby, fresh out of college, embarked on an entrepreneurial journey. Sharing an apartment in San Diego, they founded a company in 1995 with a vision to create business websites. Their venture was kickstarted with a modest $10,000 seed fund from Scott’s uncle, who also provided them with a workspace in his company, C.B.S. Scientific. This initial investment was channeled into acquiring a Sun SPARC 20 server and renting an expensive ISDN line, a significant step for young entrepreneurs.

Their business began to gain traction, securing clients and generating revenue through monthly fees. This success enabled them to move into their own office space, and in 1997, Scott’s brother, Brett Crosby, joined the team. The company was growing, attracting larger clients, yet all their websites were hosted on a single server, sharing that one ISDN line.

Paul Muret, demonstrating his programming prowess, developed a rudimentary log file analysis system. This system, initially basic, was capable of calculating website traffic and presenting it through a web interface. Gradually, he enhanced the system, adding metrics like pageviews, referrer data, and hits. This evolution marked the birth of Urchin, a simple yet effective tool for log file analysis.

Urchin’s potential was soon recognized when Brett’s girlfriend introduced them to Honda.com. Winning Honda.com as a client was a pivotal moment, as Urchin became their standard web analytics software. This success shaped the company’s future direction. Around this time, Jack Ancone joined the team as the CFO, and the company, then known as “Quantified Systems Inc.,” shifted its focus to encompass web development, hosting, and software development.

The development of Urchin continued, and in January 1998, the first professional version was released, priced at $199. This version marked a significant milestone, and soon after, a strategic decision was made to concentrate solely on software development, moving away from other business areas. This shift necessitated additional funding, and the team successfully raised $1 million to fuel their journey as a dedicated software company.

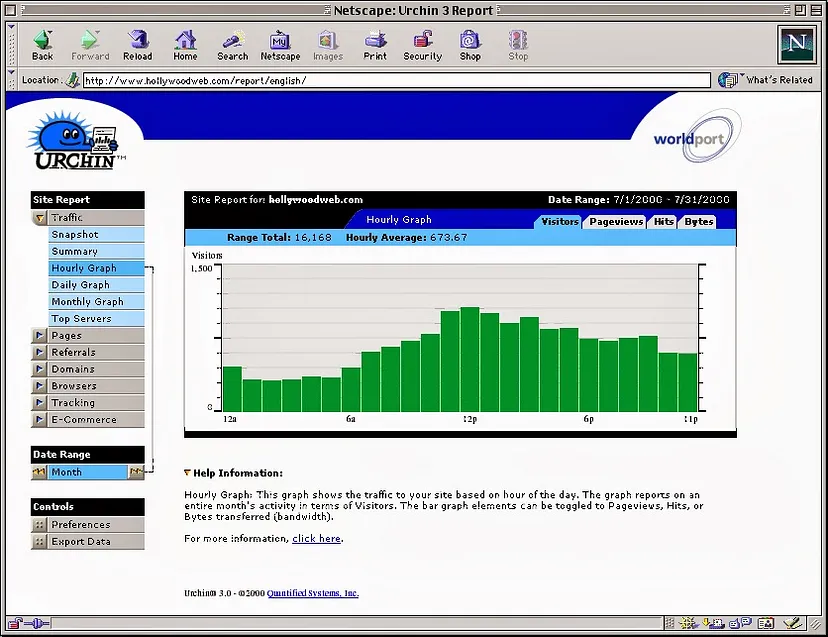

Web tracking software Urchin 2 and the evolution to Urchin 3

Early version of Urchin 2

This is how Urchin 3 website and admin looked in the past

As Urchin continued to evolve, two distinct versions emerged: the commercial “Urchin ISP” and the free “Urchin ASAP.” The latter was an innovative approach, aiming to generate revenue through advertising banners. This model incorporated both CPM (cost-per-mille) and CPC (cost-per-click) for a banner displayed at the top of the Urchin web interface. Adding a touch of creativity, there was an “Urchin of the day” feature, where the Urchin logo was regularly updated with current, sometimes animated, graphics.

In 1999, Brett Crosby took on the challenge of promoting Urchin 2.0. After considerable effort, he secured a meeting with Rob Maupin from Earthlink. Despite initial reservations about the web interface’s overly blue color scheme, Maupin decided to give Urchin a chance.

This opportunity marked a significant turning point for Urchin. With a few software modifications, Urchin was soon established as the standard web analytics software for all websites hosted by Earthlink. This partnership was not only a testament to Urchin’s growing capabilities but also a lucrative deal, with Earthlink paying $4,000 a month for the service.

By 2001, Urchin had progressed to version 3, reflecting continuous improvements and growing recognition in the field of web analytics. This version marked another step in Urchin’s journey, setting the stage for further advancements and wider adoption.

The company underwent a significant transformation, rebranding itself as the Urchin Software Corporation. During a period of flourishing business, Urchin set its sights on expansion, successfully securing a promising $7 million in funding. However, the tragic events of September 11, 2001, disrupted these investment plans, leading to unforeseen financial challenges. The company had already committed funds based on these pledges, resulting in a liquidity crisis. This difficult phase forced Urchin to make tough decisions, including layoffs and office closures. In a bid to stay afloat, they turned to affluent individuals, notably Chuck Scott and Jerry Navarra, for financial support. From 2001 to 2002, Urchin faced a strenuous period, with exhaustive negotiations and some employees even forgoing their salaries to keep the company running.

During this time, Urchin 3 was offered in various configurations to cater to different business needs:

- Urchin Dedicated: Designed for a single server hosting up to 25 websites, priced at $495, with each additional batch of 25 websites costing $295.

- Urchin Enterprise: Aimed at larger operations with 2 servers and up to 25 websites, available for $4,995, and an additional $1,995 for each extra server.

- Urchin Data Center (on request): This version was provided based on specific client requests.

Ultimately, Urchin decided to streamline its business model, focusing on simpler and more direct business deals, even if it meant earning less revenue. This strategic shift was aimed at stabilizing the company during a challenging period in its history.

Web tracking software – version Urchin 4

Demo for Urchin 4 (available only in Web Archive services): https://web.archive.org/web/20030207025325/http://www.urchin.com/products/tour/

In 2002, Urchin Software Corporation unveiled Urchin 4, a significant upgrade that sported a sleek design reminiscent of Apple’s aluminum aesthetic.

A pivotal innovation in Urchin 4 was the introduction of the “Urchin Traffic Monitor” (UTM). This feature marked a significant advancement by incorporating JavaScript tracking alongside traditional web server log file analysis. The use of browser cookies for tracking and visitor recognition laid the groundwork for what would eventually evolve into Google Analytics. Urchin 4 maintained its versatility, supporting a wide range of operating systems including AIX, FreeBSD, IRIX, Mac OS X, Red Hat Linux, Solaris, and Windows.

Web tracking software – version Urchin 5

Urchin 5 – had e-commerce/”ROI” tracking, the Campaign Tracking Module, and multiserver versions that could all conspire to get the price pretty high.

Following this, Urchin 5 was released, bringing with it notable enhancements such as E-Commerce tracking, campaign tracking, and support for multi-server environments. Scott Crosby, reflecting on this version in 2016, noted, “Urchin 4 was the first release I felt could compete with anyone in terms of back-end performance. But Urchin 5 was superior in every way, and I’m sure thousands of instances still run to this day. If anything, Urchin 5 was just too much of a good thing.”

The pricing structure for Urchin 5 was as follows:

- Base Module: Priced at $895, it included 100 Profiles (up to 100 sites) and one Log Source for each profile (additional load balancing modules required for more servers).

- Additional 100 Profiles: Available for $695.

- Additional Load Balancing Module: Priced at $695, accommodating all profiles for load balancing.

- Ecommerce Reporting Module: Available for $695.

- Campaign Tracking Module: Priced at $3995.

- Profit Suite: A comprehensive package including Urchin 5, the E-commerce Module, and the Campaign Tracking Module, priced at $4995.

Urchin 6

Image Source and Help article to Urchin User Explorer: https://support.google.com/urchin/answer/2633730?hl=en&ref_topic=2633609

Urchin 6 marked the final iteration under the Urchin brand, available through Google or authorized Urchin dealers. This version introduced a notable feature, “Individual Visitor History,” now known as “User Explorer.”

For a single license, Urchin 6 was priced at $2995, while hosting companies were charged $5000 monthly per physical data center. Notably, Urchin 6 was the first to offer a cloud solution, priced at $500 per month. This innovation contributed to Urchin becoming the world’s most popular web analysis tool by the summer of 2004, in terms of installation numbers.

During the Search Engine Strategies conference in San Jose in 2004, Google representatives Wesley Chan and David Friedberg encountered Urchin. This meeting led to Google extending an offer to acquire Urchin, despite competing offers, including a higher bid from WebSideStory. The acquisition was finalized in April 2005, a time when Google had about 3,000 employees, relatively small compared to its current size.

Installation guides for Urchin 6, such as the one for Windows, are still accessible online: https://support.google.com/urchin/answer/2591336?hl=de&ref_topic=2591275

Key differences between Urchin 5 and 6 (this was copied from the Google Urchin help):

- Major Features:

– Up to 1000 profiles (domains), log sources, e-commerce, and campaign tracking are all included with the base license; no add-on modules

– Individual visitor-level tracking, including session (path) data

– Comprehensive SEO/SEM campaign tracking features, 4 goals per profile

– Rich cross-segmenting available from most reports

– Full suite of visitor geo-location reports (not just visitor domain)

– Processing speed roughly on par with Urchin 5 but with much richer reports - Platform Support:

– Broad range of Linux platforms supported with only 2 builds (Linux 2.4 and 2.6 kernels)

– Added support for FreeBSD 5 and FreeBSD 6

– Dropped support for MacOS X and Solaris (may be reconsidered if sufficient demand is demonstrated) - Installers:

– Windows installer is now distributed as an MSI package, with better-unattended install support, integration with SMS - Configuration:

– Relational database (MySQL or PostgreSQL) administrative configuration backend

– Support for configuration database hosted on the remote configuration server - Web Server:

– Upgraded to the latest Apache 1.3.X release

– OpenSSL and mod-ssl upgraded to the latest versions

– Removed default modules not used by Urchin

– Added mod_expires for proper cache control headers - Task Scheduler:

– Scheduler now runs as two processes – master scheduler and slave scheduler

– Tasks easily managed via scripting interface to back-end configuration DB - Visitor Tracking:

– The old __utm.js tracking javascript has been replaced with a GoogleAnalytics-compatible urchin.js tracking javascript (existing sites willneed to upgrade) - Log Processing:

– geodata stored in memory (larger runtime memory footprint)

– Range of Days feature in log sources allows multi-day search for log files matching a particular date pattern

– Ability to run profiles entirely in memory - Data & Storage:

– Profile databases now default to 100,000 records/month (instead of 10,000) with the option to increase up to 500,000 records per month

– Expanded Geodata: full set of geolocation data from Quova, replaces domain-only MaxMind data

– Monthly table record limit increased from a default of 10,000 to 100,000 records

– 50 monthly files per profile, now organized by subdirectory - Reporting UI:

– Flash replaces Adobe SVG for rendering graphs & charts

– Report exporting only in CSV and XML (removed unreliable MS Word/Excel exporting)

– All Profiles report is defunct

– New visitor session/path-level reporting capabilities - E-commerce:

– E-commerce transactions can be written directly to webserver logs via special functions in the tracking javascript (identical to GA)

– External shopping cart logs in ELF2 format are also supported - Security:

– Urchin 6 has gone through a thorough quality assurance for cross-site scripting (XSS) and XSRF vulnerabilities

This is Urchin 6. Individual visitor history drill-down — potentially controversial I guess. But at least there wasn’t a “composite sketch” of the visitor. That would have been SO COOL.

Urchin 7 – groundbreaking ancestor of Google Analytics

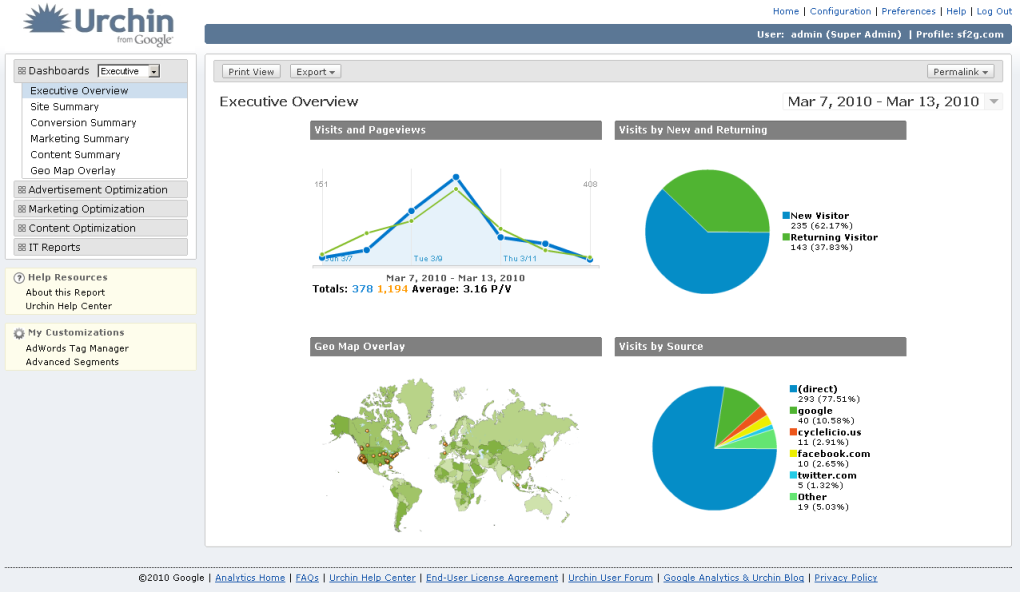

Urchin 7 – The new UI looks very similar to later well-known Google Analytics

Urchin 7 marked the final chapter of the Urchin series, now under the Google umbrella and aptly named “Urchin 7 by Google.” This version was made freely available to users, initially through an invitation-based model, leading to a rapid expansion in the use of “Urchin by Google.”

- The Help Section for Urchin 7 is still accessible:

https://support.google.com/urchin/answer/2645129?hl=en&ref_topic=2635638 - Also, the announcement of Urchin 7 is still available today (01/2021) on Google:

https://support.google.com/urchin/answer/2645097?hl=en - Many of the Urchin employees started working for Google, some even up to today. The full story of Scott Crosby is available at:

https://urchin.biz/urchin-software-corp-89a1f5292999

Many of the Urchin employee profiles are also linked there.

Appendix I: Key personalities connected to Urchin Software Company

Numerous members of the original Urchin team continue to make their mark at Google.

Notably, Paul Muret serves as the Vice President of Engineering for Analytics and Display Ads. Other team members have ventured into entrepreneurial roles, founding new companies. Below is a list of the Urchin team members over the years, presented in no particular order, along with links to their subsequent ventures where available.

- Paul Muret

- Brett Crosby — PeerStreet

- Scott Crosby

- Jack Ancone

- Scott Crosby

- Paul Botto

- Rolf Schreiber

- Jason Senn

- Jim Napier

- Hui-Sok “Nathan” Moon

- Alden DeSoto

- Jonathon Vance(s with Wolves)

- Doug Silver

- Jason Collins

- Justin Beope — Upas Street Brewing

- Megan Cash

- Christian Powell

- Nikki Morrissey

- Mike Chipman — Actual Metrics (Angelfish product)

- Steve Gott

- Ted Ryan

- Jeromy Henry

- Annie Aubrey

- Alex Ortiz

- Kelley Wilson

- Christina Hild

- David Cerce

- Ryan Walker

- Nick Mihailovski

- Bill Rhodes

- Jason Chen

- Juba Smith

- Bret Aarons

- Merrick

- Bart Fromm

- Chi Kwan

- Ed Schwartz

- Andy Smith

- Ed Petersen

- Cindy Lee

- Davee Schultie

- Joanna Rocchio

- Ben Norton

In the next article we will look more into the shift to Google Analytics/Universal Analytics up to Google Analytics 4. We will also cover the description and comparison of what is new in GA4.

Was this article helpful?

Support us to keep up the good work and to provide you even better content. Your donations will be used to help students get access to quality content for free and pay our contributors’ salaries, who work hard to create this website content! Thank you for all your support!

Reaction to comment: Cancel reply